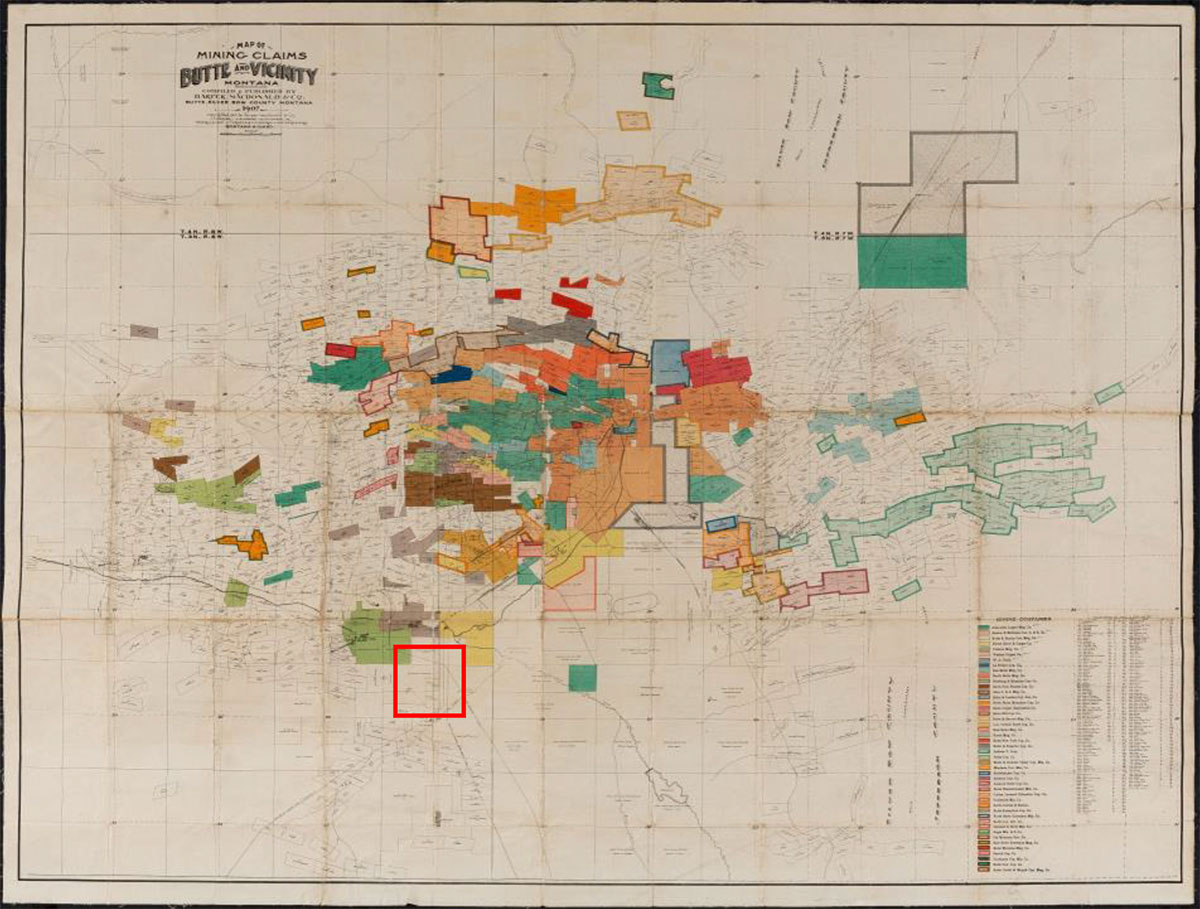

This article is the fourth essay in a series about how close reading of a map can reveal what is "Hiding in Plain Sight." The prior maps examined have been city maps, although each map was published to serve a different purpose. The Map of Mining Claims Butte and Vicinity Montana (1907)1 (Fig. 1) belongs in this series because it is a city map too, although Butte is certainly hard to locate on the map. The black letters "BUTTE" float in the dark brown color field of a mining claim that covers much of the center of Butte. The only indication on this map of Butte's downtown is an unlabeled street grid that functions symbolically as the central business district.

Figure 1. Map of Mining Claims Butte and Vicinity Montana (1907), Compiled & Published by Harper, Macdonald & Co., Butte, Silver Bow County Montana 1907. See page 15 for detail bounded by red box. Photo credit: Damianos Photography. (see also Endnote 1.)

Figure 1. Map of Mining Claims Butte and Vicinity Montana (1907), Compiled & Published by Harper, Macdonald & Co., Butte, Silver Bow County Montana 1907. See page 15 for detail bounded by red box. Photo credit: Damianos Photography. (see also Endnote 1.)

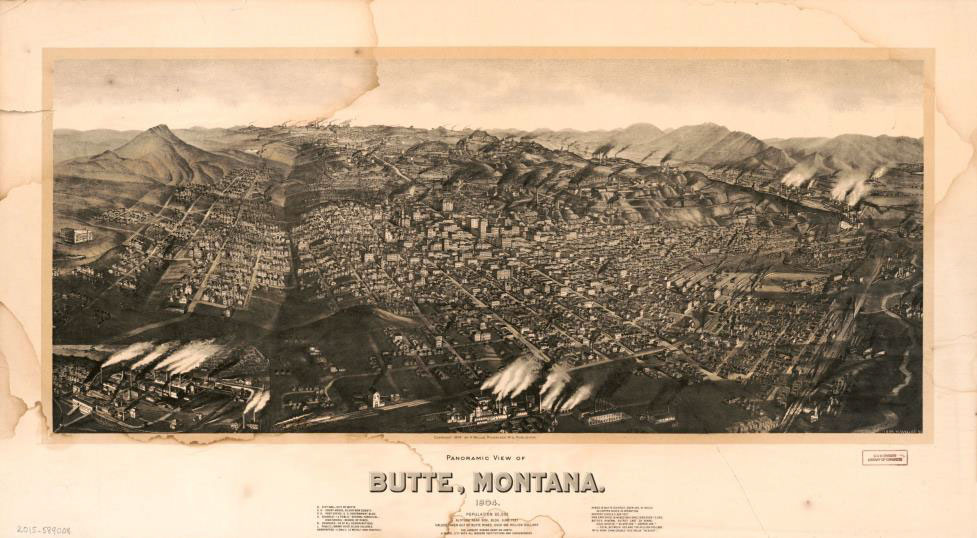

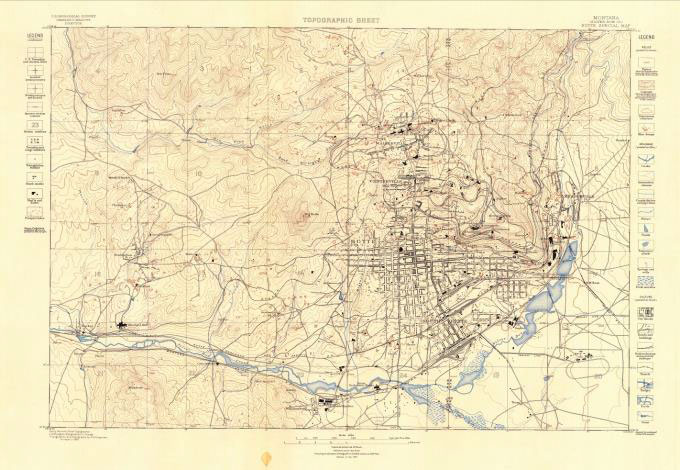

Our historic cultural focus is the American West and Butte, Montana, 18 years into its statehood. Late 19th c. and early 20th c. American Western mining town maps and birds-eye views as a genre provide one reference for our map discussion.2 (Fig. 2) Another cartographic genre for comparison is the 1897 Geological Atlas of the United States by the U.S. Geological Survey and its folios, including the Butte special folio.3 (Fig. 3) While the Butte Map of Mining Claims shares some graphic qualities of each of these genres, the Butte map is a distinct genre of "map as legal document," i.e., a pictorial documentation of legally established property interests, in this specific instance, subsurface and surface copper mining claims. Yet the Harper, Macdonald 1907 Map of Mining Claims Butte and Vicinity prompts us to consider why this mining claims map is also a city map of Butte, Montana, and what cultural history might be hiding in plain sight.

Figure 2. Panoramic view of Butte, Montana, H. Wellge, Milwaukee, Wis., Publisher, 1904. (See also Endnote 2)

Figure 2. Panoramic view of Butte, Montana, H. Wellge, Milwaukee, Wis., Publisher, 1904. (See also Endnote 2)

Figure 3. Butte special folio, Montana, U.S. Geological Survey, Geological Atlas of the United States, Atlas 38, Butte Special Folio, Montana, Washington, D.C., 1897

Map of Mining Claims Butte and Vicinity Montana (1907) is locally compiled and published by a company of inter-disciplinary mining professionals as a working map. Our map was owned first by Butte's city engineer and later by the Butte, Anaconda & Pacific R.R. engineer. This is the first edition of its series and updates copper mining claims for Silver Bow County, Montana. Butte was then known worldwide as "The Richest Hill on Earth" because of its vast copper reserves. Butte is the largest urban mining site in America. In fact, Butte ranks as one of the largest mining sites internationally.4 The scope and scale of these historic copper mining claims required railroads to transport the ore for processing and export. Thus this map also documents the rail lines serving Butte and its mining industry. The map is primarily a record of private property dedicated to copper mining. The copper mining rights are shown graphically on the map as surveyed, geometric parcels that in Butte represented coin of the realm. The 1907 Butte Mining Map is a record of the colossal, unrestricted copper mining enterprise that made possible the electrification of America and Europe.

Figure 3. Butte special folio, Montana, U.S. Geological Survey, Geological Atlas of the United States, Atlas 38, Butte Special Folio, Montana, Washington, D.C., 1897

Map of Mining Claims Butte and Vicinity Montana (1907) is locally compiled and published by a company of inter-disciplinary mining professionals as a working map. Our map was owned first by Butte's city engineer and later by the Butte, Anaconda & Pacific R.R. engineer. This is the first edition of its series and updates copper mining claims for Silver Bow County, Montana. Butte was then known worldwide as "The Richest Hill on Earth" because of its vast copper reserves. Butte is the largest urban mining site in America. In fact, Butte ranks as one of the largest mining sites internationally.4 The scope and scale of these historic copper mining claims required railroads to transport the ore for processing and export. Thus this map also documents the rail lines serving Butte and its mining industry. The map is primarily a record of private property dedicated to copper mining. The copper mining rights are shown graphically on the map as surveyed, geometric parcels that in Butte represented coin of the realm. The 1907 Butte Mining Map is a record of the colossal, unrestricted copper mining enterprise that made possible the electrification of America and Europe.

What dance before our eyes under the title Map of Mining Claims Butte and Vicinity Montana 1907 are colorful geometric shapes in a dynamic grid-like composition that resembles a Piet Mondrian painting.5 The art and cartography of Map of Mining Claims Butte and Vicinity Montana (1907), like the composition of a Mondrian painting, express a concept. The animating concept of this map is the graphic representation of competing private property rights in land: private subsurface mining and mineral property rights (mining lodes), surfaceing smaller towns are almost impossible to see due to the overlapping color blocks of mining claims. Many of the small uncolored claims on the map have fanciful names.

The color-coded key in the lower right section of the map lists forty-six mining claimants. These are America's major copper mining companies listed in order of largest claimants first. Anaconda Mining is the largest claimant, followed by Boston & Montana Cn.C. & S. Co., Butte & Boston Con. Ming. Co. et al. Small claimants are identified by survey numbers as the map key tells us their claims are "too small to name on map".

Railroads serving Butte were essential to operating the mines, the placers, and the smelters and for moving the product to market. The Butte Mining Claims Map tells yet another story of powerful real estate interests. The large railroads and the large copper mining companies were complementary monopolies. The Northern Pacific Railroad and its turnaround yard, just below the center of Butte, and the Butte, Anaconda & Pacific Railroad, a major hauler for the Anaconda smelter, are shown on the Butte map. Western railroad land grants, a means of financing the railroads, appear on this 1907 Butte map now as numerous labeled homestead claims that orbit the copper mining claims.

Not credited on the Butte map is the defining American 18th and 19th c. competition for Western land: displacement of Native Americans by westward moving American settlers, industry, and railroads that is a double play in Butte.6 Displacement took place in two stages. First, the local Montana Native Americans were displaced. Second, those Native American tribes displaced from the Eastern, Southern, and Central States who were forcibly moved to Montana were again displaced by extensive mining of Butte. The formerly Native American territory appears on the Butte Mining Claims Map as mining claims, homestead claims, and railroad lands.

The Map of Mining Claims Butte and Vicinity Montana locates and identifies primary rivers, creeks, gulches, and major geological features in black outline: the United States Continental Divide, gulches, such as the Fourth of July and Yankee Doodle Gulch, and buttes such as Butcher Butte. No mountains are shown. No contours of the landscape are indicated. No vegetation is indicated on the 1907 Butte mining map except on "Timbered Butte, elev. 5300," located south of Butte, which is drawn with trees. The absence of trees on the mapped landscape in 1907 reflects that all trees in Silver Bow County had been felled beginning in 1880 to create cordwood to fuel the smelters that burned ore to create silver and copper. By 1907 Butte and vicinity were deforested and barren of vegetation also due to mining pollution in the soil, water, and air. In 1961 and 2006, Butte was registered as a National Historic District casting parts of the city and railroads in amber.7 In 1983, Butte also became a federally designated EPA Superfund clean-up site, the legacy of industrial copper mining.8

The Butte Electric Company power plant, lines, and station are located on the map. This and other privately owned utilities provided the electrification in Butte that introduced industrial mining. Unlike the manually dug mines and wood-burning smelters of the mid-19th century gold rush in California and Colorado and the later 19th c. silver mining in Butte, by the late 19th c., electrification led to large, industrialized copper mining operations. This electrified industrial mining generated great wealth among the large copper mine company owners. Copper was in demand domestically and internationally to build out the electrification of America and of Europe. In the United States, electric copper lines added another transcontinental system.

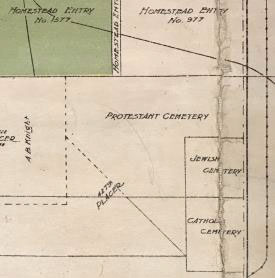

South of Butte's city center, this map shows few color-coded mining claims, most surrounding Williamsburg. The map locates one large "Brewery" and an oval "Race Track." The race track is served by the Butte Electric Railway. The brewery sits on the route of the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul R.R. and the Butte Anaconda & Pacific R.R. This sole brewery likely supplied Butte's numerous saloons and bars, where miners of copper and fortune quenched their thirst or drowned their sorrows. There is a "dump" shown on the map. There is a "Hospital". And nearby is the Lawrence A. Brown Poor Farm. The poor farm and hospital by 1910 served a population of approximately 57,000 people. Copper mining work and living in the highly polluted environment within Butte created chronic and fatal diseases. Life as a miner led to serious accidents, injury, and suicide. Many Butte residents suffered from poverty and illness. Finally, also mapped south of Butte's city center are three cemeteries, on abutting lots, labeled only "Protestant Cemetery," which is the largest, "Catholic Cemetery," and "Jewish Cemetery" of approximately the same lot size. The cemeteries lie along the main road into Butte. Abutting these cemeteries are homestead claims and one placer claim.

Detail from Fig. 1

What to make of the map's abutting Protestant, Catholic, and especially Jewish cemeteries? Rarely until the 1850s do American maps or atlases, and only certain school geographies mention or map anything but churches, cemeteries, and related population figures for the predominant American Protestant denominations. Following the large-scale Irish migration to America in the 1850s, Catholic churches began to appear regularly on maps or in atlases, with population figures noted as R.C. or Catholic. In Butte, a location with substantial Irish immigration drawn by mining work, Irish neighborhoods formed in Dublin Gulch and Walkerville. A Chinatown also existed in the central area of Butte of small immigrant businesses that are not shown on the Butte Mining Claims Map. Chinese immigrants to 19th c. Butte were not hired in the mines, although they could own placer claims. Stone masons from other parts of Europe also immigrated to Montana and settled by nationality in various towns.

Detail from Fig. 1

What to make of the map's abutting Protestant, Catholic, and especially Jewish cemeteries? Rarely until the 1850s do American maps or atlases, and only certain school geographies mention or map anything but churches, cemeteries, and related population figures for the predominant American Protestant denominations. Following the large-scale Irish migration to America in the 1850s, Catholic churches began to appear regularly on maps or in atlases, with population figures noted as R.C. or Catholic. In Butte, a location with substantial Irish immigration drawn by mining work, Irish neighborhoods formed in Dublin Gulch and Walkerville. A Chinatown also existed in the central area of Butte of small immigrant businesses that are not shown on the Butte Mining Claims Map. Chinese immigrants to 19th c. Butte were not hired in the mines, although they could own placer claims. Stone masons from other parts of Europe also immigrated to Montana and settled by nationality in various towns.

The Jewish Cemetery located on the 1907 Butte Mining Claims Map is a map element that references an established 19th c. Jewish population in Butte, Montana. Rarely do 19th-century American school geographies or atlases present any American city or state American Jewish population figures - sometimes labeled "Hebrews" as if a nationality - synagogues or Jewish cemeteries. This general absence in American maps of a growing American Jewish citizenry, especially in the early and mid -19th c. and even in the early 20th century, is a failure to represent Western migration by American settlers who were Jewish or by foreign Jewish immigrants who became Americans. In fact, there is a Yiddish immigrant's guide to the United States published in several editions.9

The invisibility of 19th c. Jewish settlement and population growth on 19th American maps, atlases, and school geographies, and even tourist maps of the Adirondacks10 were the product of cultural bias. The Butte Mining Claims Map siting of the Jewish Cemetery is one clue hiding in plain sight to the early social formation of Butte as a city.

The Jewish Cemetery located on the Butte 1907 Mining Claims Map is one of many historic memorials of the role of American or foreign-born Jewish immigrants in the settlement of Butte from mining camp to its development as the largest copper mine in the world. In 1875, Butte silver mining attracted immigrants from the American West and South, experienced miners and merchants, including Henry Jacobs (1835 b. Germany-1887) and his family.11 In 1879, the year Butte was incorporated as a city, Henry Jacobs became its first mayor. In 1885, H.L. Frank (1851-1908), an American-born Jewish settler in Butte and local merchant, became a mayor of Butte.12 In 1881, the Butte Hebrew Benevolent Society was formed on the model of the 1866 society established by earlier Jewish settlers in Last Chance Gulch [Helena], Montana. By 1894, when Butte was an urban center of unionized mine workers and a city with 17 churches, schools for 5,000 children, charitable societies, and a notorious "red light district," Butte was also a city where Jewish households were dispersed within the general Protestant population. As of 1889, Montana had an estimated 3,500 Jewish residents, a figure that defies the stereotype of only large East Coast, urban Jewish population centers.

By the turn of the century in Butte, the owners of the three largest copper mining companies, sometimes named "the Copper Kings," were American immigrants: Marcus Daly (1841 b.Ireland-1900)13 [Anaconda Mining Company]; M. Leonard Lewisohn (b.Germany1847-1902) [Butte and Boston Copper Mining Co.], Adolph Lewisohn (1849 b.Germany-1938)[Boston and Montana Consolidated Copper and Silver Mining Co.]14 By 1889, Adolph Lewisohn left business to become a philanthropist donating to colleges and other institutions including Lewisohn Hall, the first home of the Columbia School of Mines. A notorious "Copper King," Frederick August Heinz (1869-1914)15 triggered a financial panic and stock market crash in 1907, the year of our map.

An excellent body of research about Butte, Montana's settlement is the web-based The Verdigris Project,16 its name the term for the grey-green patina naturally occurring on copper as it ages. This fascinating archive holds a breadth of subject matter, media, art, and original source materials. One is the biography of Myron Brinig (1896-1991), who was a child living in Butte when the 1907 Butte mining map was published. He attended Columbia University in New York City to study literature. After graduation, Brinig returned to Butte and became a widely published author whose books, while fictional, include material and experiences from his own life in Butte, which he called "the wide open town."17

Hiding in plain sight on the 1907 Butte Mining Claims Map, at the far outskirts of Butte, the generic property blocks labeled "Jewish Cemetery," "Protestant Cemetery," and "Catholic Cemetery" are historic "land claims" of another sort memorializing the lives of 19th c. Butte residents in that "wide open town." On this 1907 Butte Mining Claims Map, the Catholic and Jewish residents are visible and lie side by side with their Protestant neighbors. This peculiar 1907 Butte Mining Claims Map is perhaps, after all, the most accurate visual representation of Butte's 19th and early 20th c. urban identity and cultural history and how it became the "Richest Hill on Earth."

- 1. Map of Mining Claims Butte and Vicinity Montana (1907) Compiled & Published by Harper, Macdonald & Co. Butte, Silver Bow County Montana 1907. Copyright 1907 by Harper, Macdonald & Co., J.H. Harper, A.B. Hobart, R.H. Lindsay, Jr., Mineral & Land Attorneys & U.S. Mineral Land Surveyors, Montana & Idaho. color lithograph, Scale 1"=1,200' [manuscript pencil above printed scale]. Dimensions: 37 1/2" x 49" sheet size and maroon pocket covers: 8 7/8" x 5 1/8" x 3/4". Manuscript inside map pocket covers: W.B. Brinker (Walter B. Brinker), the Butte town engineer 1907 and later; and "C.A. Lemmon, Anaconda, Montana" who is Charles A. Lemmon, 1916 Anaconda City Directory identified as the Chief Engineer, Butte Anaconda & Pacific Railroad.

- 2. Panoramic view of Butte, Montana, 1904: population 60,000, altitude near gov. bldg. 6,000 feet, values are taken out of Butte mines over 600 million dollars, the largest mining camp on earth, a model city with all

- 3. Butte special folio, Montana, U.S. Geological Survey, Geological Atlas of the United States, Atlas 38, Butte Special Folio, Montana, Washington, D.C., 1897

- 4. Frederick A. Heinz, please see The Copper Wars of Butte and the Invention of Underground Geological Mapping « Roger Marjoribanks Roger Marjoribanks

- 5. Mondrian Exhibit in the Hague Puts His Paintings to a Beat - The New York Times

- 6. Montana Historical Society school curriculum for the history of immigration and settlement of Montana, including the immigration of displaced Native Americans.

- 7. Butte, Montana, is on the National Register of Historic Places, U.S. Dept. of the Interior Butte-Anaconda Historic District. The historic district registration document is a description of Butte's history, settlers, neighborhoods, architecture, and environment.

- 8. SILVER BOW CREEK/BUTTE AREA | Superfund Site Profile | Superfund Site Information | US EPA; see also Google Earth aerial photograph of Butte, Montana.

- 9. Guide to the United States for Jewish Immigrants, with map, John Foster Carr, 1912. reprinted on the web at #97 - Guide to the United States for the Jewish immigrant; a nearly ... - Full View | HathiTrust Digital Library. See also for Yiddish language maps Compilation: Yiddish Cartography – The Decolonial Atlas

- 10. Amy Godine, New York histories. Amy Godine - Academia.edu

- 11. Henry Jacobs: the First Elected Mayor of Butte, Montana, 1879-1880 – JMAW – Jewish Museum of the American West

- 12. Henry Lublin Frank. Henry Lublin Frank: Pioneer Multi-Millionaire and the Second Elected Mayor of Butte, Montana – JMAW – Jewish Museum of the American West

- 13. Marcus Daly, Bonner Milltown History Center & Museum

- 14. Leonard Lewisohn and his brother Adolph Lewisohn. Adolph Lewisohn | Immigrant Entrepreneurship and Butte, America's Story Episode 120 - Boston & Montana Band — The Verdigris Project

- 15. (PDF) The Forgotten Copper Kings of Butte, America

- 16. The Verdi Gris Project. The Verdigris Project

- 17. "Myron Brinig's Butte| Jews in the wide open town" by Pamela Wilson Tollefson